Touring Germany’s Energy Village

Seeking Inspiration

Rachael and I

In February, my fiancé and I took off from Port Townsend with our bicycles and a plan to tour nine countries across Europe. For months leading up to our trip, we compiled a wish list of inspiring places to visit as the world stumbles out of this pandemic. Our dream that we are now two months into has been to travel for seven months and seek out lessons to bring home regarding our passions and respective professions within the areas of renewable energy, community housing, and regenerative agriculture. We have just departed from one of the key places that we hoped to visit: the village of Wildpoldsried, Germany. I sought out this humble Bavarian village because of its innovative and risk-taking leadership that has created an internationally known localized energy system. I aim to share what I encountered there, because what we found in Wildpoldsried was as startling as it was inspiring.

I came to know Wildpoldsried in 2015 when a local group in Port Townsend rallied together to fly Wildpoldsried’s deputy mayor, Günter Mögele, to Jefferson County for a tour of our area with the hope of learning how to apply their successes on our peninsula. Because I had the opportunity to join Günter in his meetings and presentations, my mind was opened to the reality that what Wildpoldsried has already accomplished since 2000, our local leaders could not yet imagine. Hearing Günter’s explanation of how higher electricity costs motivated the people of Wildpoldsried to take advantage of Germany’s new energy policy, it dawned on me that our lack of a cohesive national energy policy for renewables and our reliance upon hydroelectric plants and their currently cheap electricity has lured us into complacency. Indeed, depending on this aging and distant infrastructure that is dependent on regular snow and rainfall for most of our power generation may not be the best bet in a changing climate.

Overlooking Wildpoldsried’s civic centers, neighborhoods, and wind farm. Notice the solar panels?

Locally Led, Nationally Supported

Germany’s ambitious plan as set forth in their energy policy, the energiewende (‘energy transition’). This policy was designed for the nation to meet 65% of its electricity needs through carbon-free sources by 2030, and amazingly they are on track. In 2021, they met 41% of their nation’s total consumption with renewables. This remarkable, national energy transition is reflected in the village of Wildpoldsried.

Incredibly, Wildpoldsried has built a three-tiered system of local energy generation that annually produces 800% of the total village energy consumption. This doesn’t mean that individuals don’t still buy electricity when they aren’t producing enough, but the amount the village collectively uses is produced locally eight times over when annualized. The first step to this innovation is residential solar power. Nearly every other home is adorned with solar panels which power the individual’s needs first and is then dispersed into the grid. The second step is wind power, which comes in the form of a local wind farm launched by village investors who sell to the open market. The third step to their local generation is found in their local dairies which produce biogas directly from their cow’s manure, which is used to generate electricity or is fed into their district heating system. Critically, the village is completely tied to the broader grid and is served by their local utility, which not only acts as their reliable baseload, but it also receives all excess generation and distributes this valuable renewable energy across the nation.

3 MW, 450’ tall, 200 investors, €3,000,000 wind turbine project

This unassuming town has met its goals of generating 100% of its electricity locally with renewables a few times over. With their adoption of residential solar (5 MW), a local wind farm (20 MW), and dairy-fed biodigesters (2.5 MW) they meet their overall annual demand many times over. Importantly, this energy mix complements itself thoroughly: the wind power peaks in the morning and night, the solar takes the afternoon, and the biogas is used as their base load throughout the day. Witnessing this mix of renewables in-person allowed me to see the compatibility of energies and that these ambitions can actually materialize off the pages of a energy analyst’s spreadsheet.

Each of these energy projects was made financially viable by the German government’s mandate for a generous feed-in tariff for citizen generated renewable energy. The tariff sets a retail sale price of about €0.20 / kWh for the citizen and in some energies, like biogas, locks that price for 20 years to ensure payback. Another major requirement is that the electric utilities must accept this incoming energy from their customers. Both of these mandates can be found in the USA, though we’ve seen a shriveling of the feed-in tariff in Washington State, and instead of a locked-in price there is a cascading retail rate which makes it feel like unless you start installing the moment the incentives go live, you’re already missing out.

Solar, Wind, and Biogas

All three energies in one view from our guestroom

Residential solar is installed across half of the village homes. Much of the solar installation was completed over ten years ago, with many installations going back 20 years. This broad adoption was fed by a type of ‘solarize’ campaign, which is the practice of bulk buying and installing solar. This allowed the customers to leverage their costs together and seek bids from installers, rather than go out on their own. It’s not just the homes that have solar here but the public buildings, too. The initial proof of concept for most residents was seeing their public athletic center, civic club, and city hall covered in solar panels and noticing how their operational costs dropped in the process. Now, you’d be hard pressed to walk down the street and not see a home or farm without solar. In fact, most of the farmers consider their dairy farm to also be an energy farm.

Biogas is produced from five dairies in the village. The fact that they have at least five dairies is already impressive given the rapid demise of small dairies in the United States, but they’ve held on here in part because they have brought on the value-added product of biogas. Farmers can grow the grass to feed their cows, and then take that grass and other biomass, feed it into a tank and pull out the resulting methane gas. This methane is essentially an unpurified natural gas, but is distinct from conventional natural gas as it was not mined and hydraulically fracked. By deriving this methane from a waste product like manure that simply occurs when you have a farm, biogas is replacing and avoiding further use of natural gas for the farm. The biogas is also fed into the downtown district heating system which delivers space heating to local businesses, public buildings, and homes.

The farms burn this biogas to heat water which they use for their operations, including in the pasteurization of their milk, and they also heat their homes by sending it through radiators. Mostly, however, they are producing electricity with the biogas through onsite generators. This electricity is fed into the grid and the farmers are paid by the utility, who in turn is paid through government incentives to support renewables.

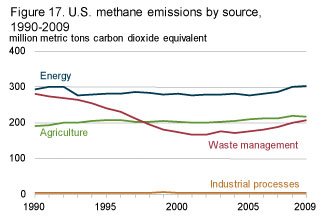

Nearly all of these methane emissions are accidental. Sourced from the EIA

It must be noted that the burning of biogas or natural gas releases carbon dioxide, but methane itself is a potent greenhouse gas when released directly through venting or leaks. And when I say potent, what I mean is that methane is at least 21x more effective as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. In actuality, most of the United State’s methane emissions are released unintentionally during the production and transporting of natural gas. Almost no methane is released when a power plant properly burns the gas but carbon dioxide, of course, is released when combusted. Indeed, much of the ‘fugitive emissions’ (blame the gas not the industry, of course) are escaping, or vented, through poorly designed or installed pneumatic controllers. This rather infuriating fact is often overlooked, yet points to the irresponsible and inconsistent nature of the fossil fuel industry which seeks to lower its costs at the expense of life on earth.

Most of the methane that currently comes from agriculture in the United States comes from enteric fermentation, which is the fancy way of saying cattle burps. So, if we’re going to enjoy the wonders of cheese, milk, and beef we need to consider how we can minimize their given emissions and how we might best utilize the unavoidable and messy aspects of their lives, namely, their crap. Lowering or eliminating our consumption of industrial meat and dairy is an obvious choice to make not only because of the treatment of the animals, but also because conventional cattle are fed all grain diets. Grain, not being a traditional food for cows, produces more methane in the cattle, so lowering our consumption of that type of meat and dairy is also important. Perhaps this is a bit off track from Wildpoldsried, but understanding the context of this energy may allow us to use it more appropriately.

Biogas dome

Dairy CHP running on biogas

The village’s primary energy source is their wind farm. This project really stands out because it was citizen led and citizen financed. In 2000, a group of local leaders, including a number of farmers, came together to form a cooperative-style enterprise that allowed them to lease land, purchase and install their first wind turbines. The first ones were relatively modest standing at 300 feet with a power rating of 1 megawatt. For this first project, 30 members brought €500,000 to the table for a down payment on the project loan. This project caught the eye of the village and two years later, 59 people came to the table to support the next one. Fifteen years after that first project, the group installed their biggest turbine yet rated at 3 megawatts, triple the capacity of the first one. Their ranks swelled to 200 investors to raise the €3 million investment. The popularity of this wind farm is fairly clear: it pays out. The investment group’s leadership decides the annual rate of return based upon how productive the farm was, and it regularly delivers an ROI of 6 - 10% annually. Try getting that at a bank.

Visiting the wind farm with ‘energy’ mayor Günter

Beyond the exciting premise of producing electricity with local projects, visiting this wind farm is a treat. It is nestled in a working forest on a ridgeline just above the village. Walking through the forest, any noise of the turbines’ circling blades is often covered by the song from native birds. It is a peaceful place and open to the public for hiking and biking. The concerns for bird safety are real and alive here, and yet this wind farm does not appear to be threatening the local inhabitants, nor have there been any documented killing of their local endangered bird of prey, which is monitored and protected by the federal government.

Not Just A Dream

Physically stepping into a living vision of our clean energy future disarmed me despite anticipating this visit for years. The idea that capable and well-resourced economies, such as ours, could have already made such a profound energy transition already seems far-fetched. This village of 2,500 has pulled off what people around the globe are clamoring for, and they did it not only because of the climate, they did it because it just makes great financial sense. Their no-nonsense approach and smart risk taking has led to their massive investment in clean, local energy and is supported heavily by strong government policies, both local and federal. Many eyes are turning to this village’s progress towards energy independence as Russia uses its grip on fossil fuel energy as a continental cudgel in Europe and elsewhere. Those participating in Wildpoldsried’s local energy generation have insulated themselves to some degree from the recent and rapid rise in electricity and fossil fuel prices. Their energy resilience has brought in international delegations for years from countries as diverse as Japan, Iraq, Thailand, Turkey, Ethiopia, and the United States. Residents of Jefferson County before me have traveled to this remarkable place and are similarly inspired to learn from and follow this village’s example.

Wildpoldsried has accomplished this energy transition by taking their future seriously, by empowering local leaders to act on a vision, and by taking advantage of the opportunities afforded to it by their government. These conditions are not a given in most places in our world. But for those of us that can see the impending change demanded by the climate crisis it is critical that we see this incorporation of local energy generation as not only possible, but an advantageous opportunity. It’s worth saying that I understand we are not Wildpoldsried, and that our energy and political situation is different. But what happens now that we know such a thing is already possible? Do we aspire for a more energy resilient community? I would like to think that I walked away from this visit with more answers than questions, but I’d be fooling myself. I am grateful for the remarkable and imperfect energy system that we do have, and in the same moment, if I squint, I can see a more resilient future ahead for us, too.

The most recent wind turbine addition from 2015

I also produced three overview videos while visiting Wildpoldsried - check them out below: